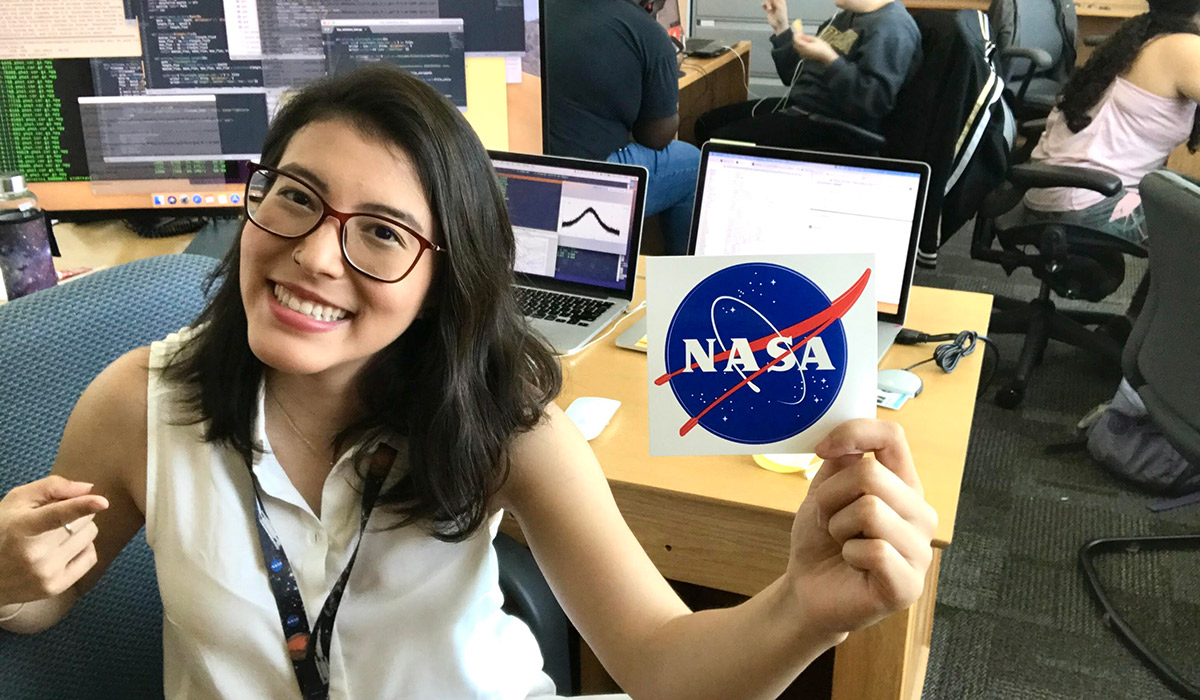

One in a million: Stela Silva, Ph.D., searches the cosmos for new planets

Stela Silva, Ph.D., an astrophysicist in the NASA Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, has her eye to the sky, sort of. Working with gravitational microlensing, which she says is "the physical phenomenon that happens when we're observing a star and then another star with a planet passes in front of it," and machine learning she looks for signatures of exoplanets.

Center: Goddard Space Flight Center

The NASA Postdoctoral Program is host to researchers from a diverse—and unexpected—range of backgrounds. From those who study the color of water, to geologists and biologists, sometimes it takes a bit of explanation to see how someone on that career path could have made their way to NASA. That’s not the case with Stela Silva, Ph.D., an astrophysicist in the NPP.

“I work very much with gravitational microlensing and I also work with machine learning,” she said recently in an interview for Further Together, the ORAU Podcast. “I'm training neural networks to detect signatures of exoplanets and the exoplanets that are detected via gravitational microlensing, which is the physical phenomenon that happens when we're observing a star and then another star with a planet passes in front of it. So we can detect it because of the gravity of this object in the middle, in between the observer and the observed star.”

The objects that can be observed using microlensing include other stars, black holes and planets. Silva and her colleagues are trying to find new planets, an incredibly rare phenomenon.

“The chances of finding one is almost one in a million when you're looking at a random star,” she said. “So, we observe millions of stars at the same time to try and detect them. That's why we are using neural networks, which is a type of artificial intelligence, to look for this data for us and try to mine through that data and find whatever is interesting for us to study.”

As a child growing up in Brazil, NASA was as distant as the stars themselves to Silva.

“I always saw NASA as something so far away. I think a lot of people in the US see it as far away, but I think if you're from another country it becomes an even more distant idea,” she said. “I always loved science. I was really good in science classes. I was really passionate about knowing how things work and what's the origin of things.”

Silva and her grandfather connected over their mutual love of astronomy, and the two would look at the night sky together.

“Fun fact: the constellations are upside down in Brazil,” explained Silva. “We see the sky upside down and we see also different constellations. I always learned about the sky with my grandpa, I always loved science classes, and I was good at mathematics, so I knew I wanted to do something related to that. But as a kid, I didn’t imagine I would one day be doing a postdoc at NASA. I think that I feel honored to be doing that, but it was so distant that I never even thought it would be possible for me. I think it got more concrete when I was really doing my Ph.D. But before that, it was just following the idea.”

When asked how the NPP has impacted her career, Silva responded that it has already opened doors for her. It has even unlocked resources that were beyond her understanding when he originally applied.

“We are talking to the top people in our field. We carry the name, so I think many people are more open to listen to what we are saying,” she said. “There are a lot of small things that we don't realize when we are applying. For example, I'm using supercomputers from NASA, and when you read the rules of NPP, you don't even realize, but you can use the supercomputers at NASA for free. That creates a huge impact in my research because I'm training neural networks, I'm doing a lot of model fittings, and if I was doing it on a normal computer, it would just take forever. But if I can do everything, I can just use the supercomputer, have my results so fast, it just accelerates the science.”

Silva acknowledges that her participation in the NPP is the culmination of years of hard work.

“It didn't happen that one day I won a lottery ticket and I was here. It was something that I constructed step-by-step. I worked hard in high school, I worked hard in college, and I worked hard during my Ph.D. And it's possible,” she said. “If it's something you want to do, work hard, be gentle, be honest. Be kind. All of those things sum up because when people see you're working hard, you're honest, you are a kind person, they put extra effort to open doors for you.”

As a young child studying the night sky with his grandfather, Silva likely thought that the chances of one day calling herself a NASA Postdoctoral Fellow were one in a million. But with every bit of hard work she’s put into his research, those chances weren’t as slim as she thought.